Tech, Bias, and Housing Initiative: Tenant Screening

Over 44 million people rent their home in the United States—and increasingly, millions of tenants and hundreds of thousands of landlords now rely on algorithms to manage rental housing. As the share of renter households grows, the market for these tools is expanding. New technology companies, enabled by large infusions of venture capital, are entering the space with algorithmic tools that have the potential to exacerbate harm, making it harder for low-income people of color to access stable affordable housing. It’s time to take a closer look at these tools—especially tenant screening tools that can be the gateway to rental housing— and the impact they have on housing accessibility.

This paper is the first in a series of working papers examining new technologies and their impacts on renters, homebuyers, and home financing. We will issue recommendations with each paper that inform a set of ethical practices and public policy solutions to guide less harmful use of these technologies within our housing market.

How Does Tenant Screening Work?

Screening tenants for housing applications is not new or unique—job applications, higher education enrollment, and housing applications have all historically required some type of screening as part of the application process. In its early days, tenant screening was a business transaction between landlord and tenant. Before the advent of automated tenant screening, landlords typically vetted tenants by having them submit their own records and references from previous landlords or others who could vouch for their trustworthiness. The emergence of automated services that comb databases for a flat fee has been a more recent development.

It Starts With a Background Check

Today, when applying for an apartment to rent, a prospective tenant usually consents to a background check by providing personal information and pays an upfront screening fee. The landlord, housing provider, or property manager then orders a background check from a tenant screening company that reports issues deemed to be relevant to the prospective tenant’s ability to pay rent and perform as a responsible tenant.

A tenant screening report can contain information from:

- Credit Reporting Agencies – To understand how a given prospective tenant interacts with banks, credit card companies, and other financial institutions, tenant screening companies use financial data from credit reporting agencies like Equifax, TransUnion, and Experian. Often, these credit reporting agencies generate revenue by monetizing the consumer insights they have, based on the financial data they collect. In a signal of how lucrative tenant screening has become, the major credit reporting agencies have all developed their own version of a tenant screening tool built off their proprietary databases.

- Data Intermediaries and Court Databases – Screening companies check criminal records for arrests, criminal court appearances, and corrections records. Court offices, commercial data vendors, and state and federal criminal record repositories possess the data that tenant screening tools consume.

When Incorrect Tenant Screening Furthers Housing Bias

Unsurprisingly, the data processed by these tools create the opportunity for discrimination. Criminal data in particular is often wrong, outdated, and delivered without important context. Even when data is accurate, much of it (such as credit reporting data) is infused with bias stemming from centuries of systemic racism reinforced by the American financial system.

As a New York Times article states, “hasty, sloppy matches can lead to reports that wrongly label people as deadbeats, criminals or sex offenders.” Sloppiness abounds as criminal records can show expunged convictions or unlawful arrests that did not lead to any charges.

The Influence of Inaccurate Eviction Records

Eviction court records are also notoriously inaccurate. In many cases, eviction records contain errors and biases that speak to the power differential that exists between landlords and their tenants. Eviction records often reflect a filing or finding, but without the details of individual cases. Background screening reports seldom include context on the dispute between landlords and tenants—whether, for instance, payments stopped after a landlord failed to make legally required repairs to the unit. Details on who is suing, which party prevailed, whether the case was settled and if the case was ultimately dropped are essential for understanding whether someone can be a good tenant, but are often left out when considering someone’s eviction record. Prospective tenants have to overcome immense obstacles to clear their name and find a landlord who is willing to look past their background check and evaluate them based on specific, personal circumstances.

Tenants are much more likely to not have legal representation in eviction cases, tipping the scales strongly in favor of the landlord. Research finds that approximately 90% of landlords in eviction proceedings have legal counsel while 90% of tenants do not; without representation, tenants are far more likely to lose their case. More is at stake here, as a single eviction dispute can land a tenant on a “black list” that translates to repeated, automatic denial in the case that a landlord uses a tenant screening service.

Eviction filings often occur on unfair grounds and may not be an indication of a renter’s behavior or ability to pay. For example, tenants are sometimes evicted if the police arrive because they are the victims of a crime; this is common enough that many states have passed laws explicitly preventing the eviction of survivors of domestic violence. Still, if someone was evicted prior to the passage of such laws, the eviction record can follow them around in perpetuity.

Given the financial instability the pandemic has caused, extenuating circumstances such as an unstable job market and sudden change or loss of employment introduce rent and mortgage hardship that belies previous payment history. Black and Latinx families have experienced higher rates of rent hardship and inability to make mortgage payments when compared to white families. In the face of all this, and in the absence of important context about a potential tenant’s background, landlords opt not to rent to people with low credit scores, or criminal or eviction histories—characteristics that are correlated to race due to the systemic racism in our economic and criminal-legal systems.

Predatory Financial Systems Decimate Credit Scores

Addressing the bias in credit scoring requires dismantling financial structures that excluded and actively preyed on Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color, therefore withholding their credit-building opportunities. Throughout the twentieth century, banks have redlined Black and Latinx neighborhoods by refusing to locate branches in low-income neighborhoods of color. This deprives neighborhoods of conventional loans, despite the legal obligation for banks to meet the credit needs of the communities they serve.

Additionally, deregulation in the 1980s paved the way for a “fringe financial system” that consists of high-interest products and services, such as predatory check-cashing and payday loan businesses that destabilize communities of color and contribute to a growing racial wealth gap. Beginning in the 1990s, banks issued predatory mortgages to applicants of color, creating the conditions for the financial crisis of 2008 to disproportionately decimate wealth in households of color. “Waves of foreclosures hammered neighborhoods of color” and consumers resorted to high-rate credit cards to cover basic living expenses, bolstering a debt-collection industry that preys on people saddled with debt. Courts were then used to issue judgments that reinforce a vicious cycle of lowering credit scores.

Risky financial products and predatory loans often lead to higher delinquency and default rates because of the harsh fine print designed to penalize. Credit scores were touted as a “great equalizer” in being a non-discriminatory way to measure risk, but is actually built upon the lending and finance systems that have taken advantage of consumers who seek credit under more volatile financial circumstances. A credit score is a measure of one’s income and banking status over a lifetime; with the nation’s wealth concentrated in white households and a financial system that continues to target people of color only to penalize them when they can’t meet predatory financial terms, a credit score becomes, in many instances, a proxy for race.

How Automated Screening Exacerbates These Harms

Fair Chance housing experts and advocates, such as the National Fair Housing Alliance (NFHA) and Upturn, have sounded the alarm about the wide-ranging impact and exclusionary nature of automated tenant screening. While landlords have historically engaged in many discriminatory practices and behaviors, automated screening reports amplify harm at a scale never before seen. Cities have taken notice—Fair Chance Housing laws are gaining traction. Within the past five years, cities like Portland, Detroit, Minneapolis, St. Paul, Oakland, Washington D.C., and Seattle have passed laws that lower barriers to housing for people who were previously arrested or incarcerated. For example, Seattle’s 2017 Fair Chance Housing legislation is widely considered a gold standard because it forbids landlords and tenant screening services from requiring, disclosing, inquiring above, or taking an adverse action “against a prospective occupant, a tenant, or a member of their household, based on any arrest record, conviction record, or criminal history.”

VCs Enter the Chat: Promises Abound (And So Do Perils)

Rentership levels in the United States are at their highest since 1965. Investors see a market opportunity to automate rote, time-consuming rental procedures such as tenant screening and consolidate them onto a single technological platform for landlords and renters to use. Venture capital firms exert a growing influence on the $1 billion tenant screening industry. As startups explore the tenant screening space, some choose to focus solely on running tenant reports, while others offer a suite of software tools for rental property management or communication tools for landlords and their tenants. Venture-backed companies play an increasingly influential role in granting access to housing; it is necessary to understand how technology that produces contextless thumbs-up, thumbs-down recommendations amplifies cycles of harm and has a disparate impact on tenants of color.

Tenant screening companies promise algorithm-driven assessments and recommendations that can be generated and delivered to a landlord’s inbox, in less than a minute. On their marketing pages, tenant screening companies purport to paint a holistic picture of rental applicants, claiming no damage to the tenants’ credit score, and promising privacy protection.

The following screenshot from TurboTenant gives a sense of the thumbs-up, thumbs-down, and color-coded recommendations that tenant screening companies provide.

Companies emphasize how their proprietary technology makes impartial decisions using aggregated insights from their proprietary data—their models can take a tenant’s individual characteristics, such as the risk of defaulting on rent, and compare it against the risk for the average prospective tenant living in a particular zip code. They do not, however, provide transparency or context for how their conclusions are drawn.

“Black Box” Tenant Screening and the Cycle of Housing Instability

Despite the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s guidance and Supreme Court rulings that using criminal history to deny housing violates the Fair Housing Act, people impacted by the criminal-legal system continue to be screened out of housing. Using the criminal-legal system to determine housing eligibility will reproduce the racial disparities inherent in the system. Criminal-legal databases include information not just about convictions or sentencing, but also about arrests. Arrests are merely a suspicion of criminal activity, not proof of misconduct. Certain tenant screening companies may not distinguish arrests from criminal convictions, or convictions from 20 years ago from more recent ones. Because Black and Latinx communities are over-policed, tenant screening technology that incorporates court records will have a disparate impact on Black and Latinx potential renters and their families. It also creates a secondary market of so-called “second-chance” landlords, who will rent to people with unfavorable background checks and use them as grounds to charge extortionist rates for things like security deposits, strapping a vulnerable population with even greater debt.

Furthermore, generations of exclusionary lending have locked local Black, Latinx, Cambodian, and Pacific Islander communities out of housing. This creates a vicious cycle in which people returning to their communities are unable to secure the stable housing necessary to obtain good jobs or educational opportunities, leading to more evictions, homelessness, and likelihood for rearrest. Thus, a previous conviction functions as a “modern-day scarlet letter” for many American renters, as prospective renters of color bear the brunt of being on renter black lists that all tenant screening companies reference.

Modern Fair Housing guidance asserts that housing applicants have the right to mitigate adverse screening decisions by providing landlords with explanatory information about their criminal histories before their housing application denial. Yet tenants cannot exercise their fair housing rights if scores and leasing decisions are obscured by proprietary “black boxes,” when even landlords cannot be sure if the screening technology is advising a “No” determination because of their credit score, criminal history, or some other reason.

Background checks run the risk of using incorrect or outdated information for their screening report. They may incorrectly or partially match names, refer to expunged or obsolete records, or flag an arrest instead of a conviction. Since most tenant screening companies source raw data from the same few data reporting companies, prospective tenants find themselves repeatedly denied housing on baseless grounds and often end up in insecure housing conditions that could jeopardize employment opportunities. In these cases, the Fair Housing Act is difficult to enforce since landlords are unlikely to conduct an individualized assessment of prospective renters if they’re unaware that the applicant was rejected based on a criminal history.

Approximately 2,000 tenant screening companies exist without being registered to or reporting their decisions to government agencies. Given the cheap availability of electronic civil and criminal court records across the country, sex-offender registries, terrorism watch lists, and housing court records the barrier to entry is low. Virtually any team with modern technology and basic coding skills could control the housing destiny for countless prospective tenants. Individual companies play by their own rules, using internally-driven, proprietary rules to conduct the background check and provide a recommendation. The lack of resources and guides to implement standards and accountability in cases of inaccurate screening is concerning, to say the least.

Even if tenants are able to dispute an incorrect background check, the best they can usually hope for is to be put on a waiting list for the next available unit, as landlords likely have already assessed and rented to the next applicant in the virtual application pile before the first tenant realizes they need to dispute their determination. Until there is a major overhaul of the matching and search criteria, many families will be trapped in a cycle of housing instability and eviction. These outcomes exacerbate the racial wealth gap as families of color devote a burdensome share of their income to rent.

As hundreds of thousands of housing providers, landlords, and property owners opt to use third-party tenant screening to simplify their tenant selection process, these companies are now the gatekeepers of housing access and opportunity. Given how error-prone tenant screening reports are, a sizable number of renters will face technology-driven housing precarity each year.

What Laws Currently Protect Tenants and Landlords from the Pitfalls of Screening? What Are Their Shortcomings?

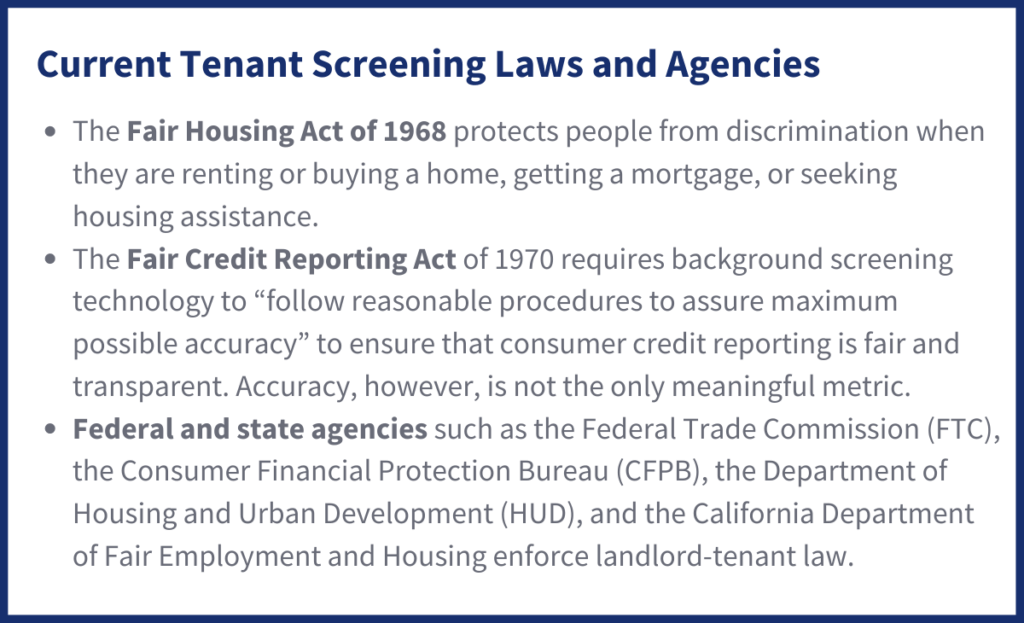

The Fair Housing Act of 1968 protects people from discrimination when they are renting or buying a home, getting a mortgage, or seeking housing assistance.

- In 2015, the Supreme Court ruled that landlords are responsible for assessing the individual circumstances, rehabilitation, and nature of the record before denying an applicant due to their criminal history— a process known as an Individualized Assessment.

- The Fair Housing Act outlines the procedures to file individual discrimination complaints. Tenants are entitled to the ability to pursue legal action if they believe a housing provider is disproportionately denying people with protected class status. Prospective tenants can not be barred from housing without justification or their legal right to an individualized assessment. In practice, however, tenant enforcement of the Fair Housing Act through lawsuits is time intensive and cost-prohibitive, with no requirement that a unit be made available to them even if successful in court.

- First approved by the Supreme Court in 1982, fair housing groups engage in Fair Housing Testing to investigate and yield evidence of a pattern or practice of illegal housing discrimination. Information gathered from site visits can be used as evidence for a housing discrimination complaint.

Effective in 1970, the Fair Credit Reporting Act requires background screening technology to “follow reasonable procedures to assure maximum possible accuracy” to ensure that consumer credit reporting is fair and transparent. Accuracy, however, is not the only meaningful metric.

- Because of highly correlated links between favorable credit and whiteness, low-income renters of color are much more likely to be screened out of housing altogether.

- Despite these codified fair housing protections, tenants must possess proof of overt discrimination or data proving their landlord’s practices disproportionately screen out protected classes—the exact information that new screening services omit.

Additional agencies that enforce landlord-tenant law:

- At a federal level, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) field requests to update inaccurate or outdated information on tenant profiles.

- The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) receives housing discrimination complaints about Fair Housing Act violations or discrimination within HUD-funded housing and community development programs.

- At a state level, renters can file discrimination complaints through the California Department of Fair Employment and Housing.

Despite a number of enforcement agencies, discrimination is still rampant in the housing market. Leaving the protection of civil rights up to the tenant—often through costly legal action or lengthy bureaucratic labyrinths—ensures that only those with the time and resources are able to pursue justice. Under this legal framework, we’ve seen Black homeownership hit a lower rate than before housing discrimination was illegal. Even before the proliferation of technical and opaque housing tools, the country’s housing protections enforcers were underprepared to address the scale of housing injustice. Our 20th century laws are thus woefully insufficient to regulate twenty-first-century technologies, leaving vulnerable tenants even worse off.

How to Fix It

Fair housing laws should be the baseline for preventing discrimination. In practice, they are the ceiling. What are the remedies for this?

Mitigate risk through data transparency

Both landlords and tenants should receive detailed screening results, including the factors that informed each individual assessment. Without full transparency into the data used to create their screening report, prospective tenants cannot exercise their rights under housing anti-discrimination laws and therefore have no recourse when they are unjustly denied housing. Landlords are also exposed to risk. Without context, they may illegally deny housing to applicants based on factors heavily correlated with race or other protected characteristics.

Additionally, tenant screening companies should publicly disclose how they aggregate records and clean consumer data, especially when they are from third-party data vendors. Prospective tenants that possess profiles in a tenant screening company’s database should be able to clarify and scrub any inaccurate or outdated information.

Perform regular audits on outcomes

Companies should test their tenant screening technology outcomes against traditional screening methods with human review to evaluate whether this technology is more predictive of a tenant’s ability to pay rent and abide by the lease. Breaking down the outcomes along certain variables like race, gender, country of origin, and income will help identify if there are inherent biases baked into the model. Ideally, a third-party regulator should have access to these outcomes and receive a report of rejected applications.

De-bias products and platforms

Tenant screening companies are long overdue for a product overhaul. Especially as these screening companies monetize renters across their lifecycle and convert them to homeowners, companies should rethink how their products impact housing access and opportunity. First, they should incorporate product features that mitigate common forms of bias. An example of a de-biasing product technique is “Distribution Robust Optimization (DRO),” which “minimizes the worst-case loss of each group in the dataset,” as opposed to minimizing average loss. DRO can be used to de-bias outcomes where historical and human bias occurs (e.g. when predictive algorithms target neighborhoods of color due to decades of racist over-policing catching ‘more crime’ and reinforces the decision to patrol these neighborhoods due to higher arrest rates). Companies that use machine learning models with high overall accuracy, but low accuracy for underrepresented groups, should use DRO to de-bias their tenant screening products. Additionally, they should be training landlords on the unintentional but real bias that exists and how to use the scoring as an advisory.

Strengthen federal regulation

Currently, state and local ordinances regulate tenant screening more tightly than the Fair Credit Reporting Act. For example, in Oakland, CA, if a landlord moves to reject a prospective tenant, the tenant must have instructions to file a complaint, receive a list of legal services, and understand the basis for the decision with an opportunity to respond.

To illustrate, California’s Department of Fair Employment and Housing recommends that whenever a criminal conviction comes up, the prospective tenant should have the ability to undergo an individualized assessment. An individualized assessment weighs all relevant considerations from an individual’s conviction within a certain timeframe, known as a lookback period. Housing providers should narrowly tailor their assessment on whether the criminal conviction is directly related and provide the applicant the chance to share “mitigating information” in person or in writing. Sample individual characteristics could include:

- How recently the criminal offense occurred

- The nature and severity of the crime and the sentencing

- The age at which the crime was committed

- The length of time that has passed

- Evidence of rehabilitation

Housing worthiness should not be determined solely by a credit score or a set of past actions. Federal regulation needs more teeth to ensure that all tenants, not just those who have criminal histories, have an opportunity to utilize an individualized assessment. One’s right to housing should give prospective tenants the chance to explain their prior behavior, and demonstrate their ability to be a good tenant. Tenant screening companies should ensure that prospective tenants understand how to file a complaint, have a chance to communicate with the landlord about their individual circumstances, and be guaranteed the opportunity to provide context for any eviction filings that appear on their record.

Commit to best practices

Many housing advocates and consumer protection organizations want tenant screening companies to stop issuing blanket recommendations that hinder the ability for landlords to conduct an individual assessment. Given that convictions become less relevant the older they are, tenant screening companies should shorten their lookback periods on a background search, as a record from many years ago likely has decreasing relevance and impact.

Recommendations for Best Practices for Tenant Screening Companies

Precedents established by regulators, companies, and advocates in the fair employment background check space can be used to hold tenant screening accountable. While most tenant screening companies don’t seem to be motivated by the idea that housing is a human right, there are companies like Checkr that have outlined tenant screening best practices for landlords that use their screening software, notably:

- Run a background check only with permissible purpose.

- Wait until the end of the application/renewal process to run background checks.

- Inform the candidate or tenant when taking negative actions such as rejecting a tenant application

- Individually consider offenses found in a report; don’t automatically deny based on any offense.

- Give candidates/tenants a chance to explain offenses that were found, and consider those explanations and circumstances as part of the evaluation process.

In addition to the best practices outlined by Checkr, tenant screening companies should:

- Provide tenants with all files and records that contain their name.

- When recommending adverse action for a prospective tenant, include the rationale for adverse action

Where Do We Go From Here?

Tech-enabled screening companies operate against a backdrop of discriminatory housing policies and practices, both past and present. Opaque tenant screening tools are increasingly prevalent, creating harm through their inaccuracy and incompleteness. When housing providers reject tenants based on inaccurate screening reports, landlords are at risk of violating fair housing laws, especially when they don’t have access to granular data. More data transparency translates to better fair housing enforcement. Landlords need it to do the right thing and regulators need access to proprietary data to hold tenant screening companies accountable. Current legal frameworks, as they stand, are limited in their ability to protect tenants’ rights to fair housing.

Housing rejections are consequential—they stifle housing opportunities for generations to come. If screening companies are not more proactive about monitoring for risk, impact, and equity throughout the creation and growth of their companies and products, they will widen the already gaping housing disparities that exist. We believe that a vital first step is understanding the historical conditions that created the housing shortage and inequities that we observe today.

The next papers in the Tech, Bias, and Housing Initiative series will further examine the ways in which new housing technologies and companies support or undermine the principle of housing as a right for all people to access. As we continue our research efforts, we hope to educate our community on emerging technologies entering the housing market (e.g. predatory homeownership schemes, exclusionary real estate listings, and hard-coding exclusionary lending) and their potential impact on the most vulnerable renters and homeowners.

Do you work in tech-enabled tenant screening and want to share research and recommendations for better corporate practice? Contact us at info@techequitycollaborative.org.